*Sarah Northway fans: Email me at [email protected] for a 50% coupon code good for subscriptions to Hardcore Droid. ~ed.

I’m an independent game developer. Independent from publishers, independent from bosses, from 9 to 5 work schedules and commutes and possessions and national boundaries. Since I went indie in 2011 I’ve lived in 15 countries and released five games, including the post-apocalyptic strategy series Rebuild.

I know my experience isn’t the norm but if you’re keen to do the same I can tell you the steps I took to get where I am now.

Step 1: Love Games

In 1988 I was 8 years old and saving up for my first big purchase: a NES with a light gun, Duck Hunt and Super Mario Brothers. One afternoon of smushing goombas and I was hooked for a lifetime. Forget TV and books (or God help me, sports or makeup). Give me my video games!

In my awkward teens I got deep into the vast open worlds of pc games like Sim City, Civilization, the Elder Scrolls and Might and Magic. Through them I learned how to navigate DOS, connect soundcard drivers and write batch scripts. I loved computers because they were full of little puzzles and let me play games but I knew the games industry was a very exclusive club of brilliant and hard working people. I believed if I was ever lucky enough to become a game developer, that video games would lose their magic and the last thing you’d want to do after working on games all day would be to play one.

I was wrong, But more on that later.

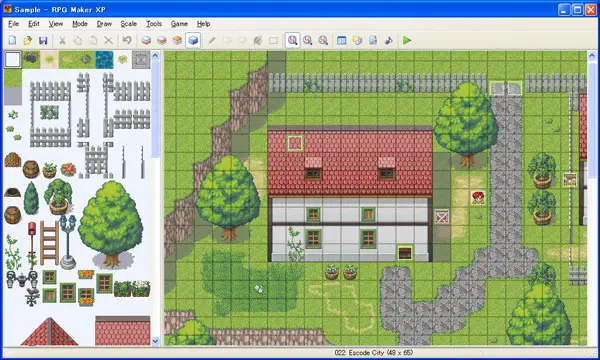

So I never made games as a kid but I’d write embarrassing Wizardry fanfiction and make custom Warcraft maps and detailed Tolkien-ripoff worlds in RPG Maker. That motivation to be creative and make stuff is super core to being an indie dev. I think it’s all you absolutely really need and everything else will follow.

With the advent of the Internet I started designing pretty websites and filling them with my opinions (and the occasional rare pirated game from Japan). It got easier to find the weird niche games I had a taste for: stuff like roguelikes, quirky sims and artificial life games. You couldn’t find them on store shelves because AAA publishers wouldn’t risk printing all those boxes and having nobody buy them. This is where indie games and Internet self-publishing came in. Suddenly you could write a game about anything – say, raising beavers on the moon—and somebody across the world who shared your interest in space beavers could buy it. But still, I thought, you must have to be crazy smart and lucky and at the very least have an expensive education to make games.

Wrong again.

Step 2: (Don’t) Get an Education

So I went to college and got my Bachelor of Computer Science, because that’s what you do after high school. It was expensive and hard work and it took four years that I wish I had back. I had classes on programming and circuitry and math and more math, and plenty of basket weaving courses like medieval studies and history of film. I slept through half of it, crammed for tests and learned very little.

But oh, that piece of paper, that CS degree companies need to see on your resume. Proof that you’re a smart cookie and you’ve “learned to learn,” and you can put your head down and shovel shit when you need to, which is a useful skill to be honest.

I did love the projects in my few software classes. We got to actually make things instead of just theorizing about them, and I learned new concepts so easily (recursion! OOP! databases!) when I could tangibly apply them to a real project. Obviously I learn best by doing. If I was going to do it again, I’d split two years between a programming trade school and writing my own games. Today there are video game schools to consider too. Most game companies would rather see a solid CS degree on your resume than an artsy “game dev” one but who cares if you want to go indie and be your own boss? Just don’t waste your time drifting through an education that costs a fortune and doesn’t teach you anything!

At least I had fun in college. There were great parties and I met my future husband Colin Northway, who’s also an indie game dev now. I had my pick of the lot, since in 1998 girls were rare in our CS program. I never really thought about it except in our huge, totally deserted women’s washrooms. I’ve never felt different or oppressed because of my gender. If anything it’s been a boon because it makes me a little more memorable as an indie dev, and in this business personality helps sell games.

I graduated in 2001, just as the dotcom bubble burst and all the tech jobs disappeared. Colin and I took pathetic webdev contracts for failing small businesses, happy to have any income at all and to be able to work from home on our own schedules. And we continued our student’s diet of cheap ramen noodles and mac & cheese — important training for an indie dev.

What I should have done is taken time off to write a game in Game Maker or Flash or Unity. That’s what game companies really want to see on your resume since it shows both your motivation and talent. But I was still skeptical that regular people like me could make games for a living.

Step 3: Make Games

By 2006 we’d found good webdev jobs, but after a decade in the same town we started getting itchy feet. We saved up to take a belated gap year: half on a quiet beach in Thailand and half in the bustling cities of Japan. Thailand was exactly as amazing as it sounds; exotic and beautiful and inspiring. But after a few months anything can get boring.

So I started writing a game in my spare time as a way to work on my Flash and Java skills. It was a huge, overambitious MMO that I had no intention to finish, release, or even show to anybody.

Turns out this happens a lot. Indie devs get so scared of releasing their games that they subconsciously sabotage them, letting features creep in and adding months or years of development. It’s so important to know the scope when you start working on a game. Will it be a three-month game? A six-month game? What needs to go in it and what can wait for the sequel? When will you show it to friends and family? Do you release in beta and make constant updates (the Minecraft model) or release version 1 for free then write a sequel (the Rebuild model)?

Anyway, my unfinished MMO did help me get a job at a games company called Three Rings when we made it back to civilization. I had a crazy good time working with incredibly smart and talented people on games like Puzzle Pirates and Whirled. All my creative energy went into my work there.

Meanwhile my (now-husband) Colin took a more tedious webdev job which left him bored and unfulfilled, so on weekends he wrote games. He released his Flash physics game Fantastic Contraption in 2009 with no press, barely deigning to distribute the demo and charging $10 almost as an afterthought. But it was a viral hit, pushed to the top of the ranks on StumbleUpon and suddenly it had hundreds of sales a day.

Miracles happen but usually it’s up to us indies to do marketing, stoke community fires and push our games onto every conceivable platform. Publishers might promise to do some of this for you but those promises are rarely worth the percentage they take and they aren’t going to care half as much about your game as the game’s creator would.

Step 4: Be Flexible

There’s a lot more to being indie than just making games: marketing, bizdev, tech support, community management. That’s all me. I spend an hour a day just answering emails. Even in bigger teams it’s unlikely you’ll have someone dedicated to this stuff, so it’s DIY all the way. But that’s the fun of being indie; you’re always trying new things and learning new skills.

After a few years at OOO (Three Rings… get it?) we got itchy feet again and left to travel once more, this time while writing games for profit instead of just fun. We sold everything except our backpacks and laptops and started in Europe this time around. We spent two weeks here and a month there, watching boats on the Bosphorus in Istanbul, touring Czech castles with friends, hiking through vineyards along the Italian Riviera and visiting Colin’s relatives in bonny Scotland.

We worked on our games as we went, and we’re still at it three years later with no plans to settle down. Indies can work from anywhere in the world, so why not from a beach in Mexico or a cafe in Vienna? Travel is affordable so long as you stay long term and aren’t paying for an apartment back home.

I wrote Rebuild in 2010 as a free Flash game and auctioned it off for sponsorship money on FlashGameLicense.com. I planned it as an easy three month game: a simple strategy/simulation in a zombiepocalypse setting that seemed overdone, yet never done right. I didn’t want to shoot zombies; I wanted to hear the survivor’s stories and feel the responsibility of keeping a band alive under desperate circumstances. I created Rebuild because I wanted to play it. A lot of features had to be put aside to get it done in three months, but luckily the first game was successful enough that I could afford to make another. And another.

Between them I wrote a word game called Word Up Dog, which was a heartbreaking flop. With indie games sometimes you eat the bear, and sometimes the bear eats you. Maybe I’ll never have another successful game and I’ll have to go back to contract work. Or maybe Rebuild 3 will be a huge hit and I’ll be set for life. Even the most successful indie games take a combination of talent, hard work and (primarily) luck. Nobody gets into indie games to make money. We do it because we love it.

And we do it for the freedom it gives us. Freedom from publishers, sure, but also freedom to roam the world and work from the jungles of Honduras, the beaches of Costa Rica, and over the dazzling coral reefs of the Philippines. Next Colin and I are headed for three months in Bocas del Toro, Panama. It’s not a vacation; this is being indie.