You don’t see a lot of momentum-based games nowadays. You do, however, see a lot of pretentious ’80s throwbacks: see Vaporwave or the recent revival of ’80s drum machines in pop music for example. Now, like any hipster degenerate, I love me some Duran Duran, but I’m beginning to consider that this focus on late-’80s/early-’90s culture has to be unfair to those who actually experienced those times. Those who are not only sick of cheesy synths, but have to contend with everyone under the age of 25 raving woefully about the endlessly hazy neon party that 1988 definitely wasn’t. But, as far as momentum-based games go, there’s been a sore lack. My time spent playing Tribes constitutes some of my better gaming memories. That feeling, even in a virtual space, of cresting the top of a hill to sprint down, sling-shotting yourself into what feels like low-level orbit; it never fails to tap into a primal adrenaline, when done well. When done okay, there’s still a rush in going fast, I suppose, but as usual, player control is everything.

You don’t see a lot of momentum-based games nowadays. You do, however, see a lot of pretentious ’80s throwbacks: see Vaporwave or the recent revival of ’80s drum machines in pop music for example. Now, like any hipster degenerate, I love me some Duran Duran, but I’m beginning to consider that this focus on late-’80s/early-’90s culture has to be unfair to those who actually experienced those times. Those who are not only sick of cheesy synths, but have to contend with everyone under the age of 25 raving woefully about the endlessly hazy neon party that 1988 definitely wasn’t. But, as far as momentum-based games go, there’s been a sore lack. My time spent playing Tribes constitutes some of my better gaming memories. That feeling, even in a virtual space, of cresting the top of a hill to sprint down, sling-shotting yourself into what feels like low-level orbit; it never fails to tap into a primal adrenaline, when done well. When done okay, there’s still a rush in going fast, I suppose, but as usual, player control is everything.

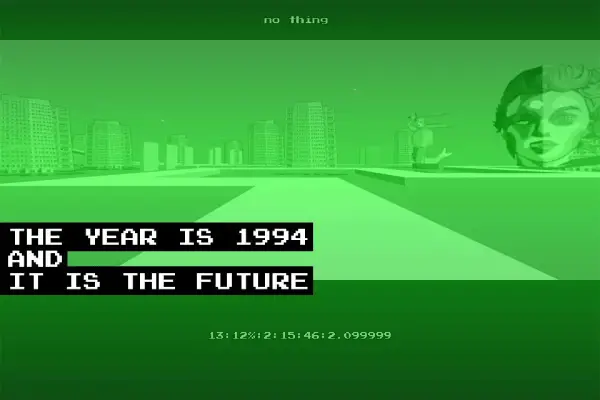

Evil Indie Games’ NO THING is an endless runner where you navigate a racetrack suspended in Vaporwave camp and VHS distortion, only able to turn left or right by 90 degrees. The more you turn, the faster the game gets, and the harder it is to stay on track. By itself, there is no issue, but compared to other games where momentum-building is a central mechanic, it’s flaws become wholly apparent in one area: You don’t control speed. Gliding down snow-glazed hills required skill and continuous input in Tribes, which I bring up again because the title’s mere mention gives me goose-bumps; yet in NO THING, the game is in complete control of how fast you go at any given time, and it creates a gap in agency that should have been filled by the player.

Just imagine how much fun it would be if the game consistently increased momentum with every turn, without that speed arbitrarily plateau-ing: You would have further incentive to find tricks to turn more, and more importantly, the player would be empowered to shape the experience around their own skill level, where they could increase momentum in big chunks or minute steps. This is no small issue, because allowing a character to feel as though progression is a consequence of their actions is a fundamental aspect of game design.

This doesn’t mean that the game is bad, just that it makes some crucial missteps from being perfect. I will say, on another note, that I love the visuals. The bleeding colors, hazy saturation, sudden palette shifts and glitches not only enforce the game’s cudgel-delivered motif, but also create sudden bursts of challenge as half your screen is obscured by glitching. In most games this would feel cheap, but here it instead forces you to note your surroundings and always be prepared to know just when to turn away from a bottomless pit, even if you’re unable to see the path ahead. The disembodied voice-over struck me as droning, annoying and pretentious, but the disembodied low-poly heads were definitely rad, and made the game feel that much weirder. A shame we didn’t get any twelve-vertices Reagans (as far as I could tell), but eh, there’s always room for a sequel.

Hardcore?

Sure.

An endless runner with great style that fumbles a bit in execution.