War and video games go hand in hand. How many Call of Duty games have they made? Certainly more than there have been American wars. Call of Duty, Battlefield, Warcraft, Starcraft, Age of Empires, Halo; war games are undoubtedly the biggest and most popular games there are. And for good reason. War is exciting, when it’s a fantasy. There’s conflict, drama, high stakes, epic struggles that span the globe. It’s everything that makes for a memorable experience. It pulls you in, jacks up your heart rate, and cramps your fingers. Your blood pumps, your heart beats like crazy. Have to fight. Have to win. Ra! Ra! Ra!

War and video games go hand in hand. How many Call of Duty games have they made? Certainly more than there have been American wars. Call of Duty, Battlefield, Warcraft, Starcraft, Age of Empires, Halo; war games are undoubtedly the biggest and most popular games there are. And for good reason. War is exciting, when it’s a fantasy. There’s conflict, drama, high stakes, epic struggles that span the globe. It’s everything that makes for a memorable experience. It pulls you in, jacks up your heart rate, and cramps your fingers. Your blood pumps, your heart beats like crazy. Have to fight. Have to win. Ra! Ra! Ra!

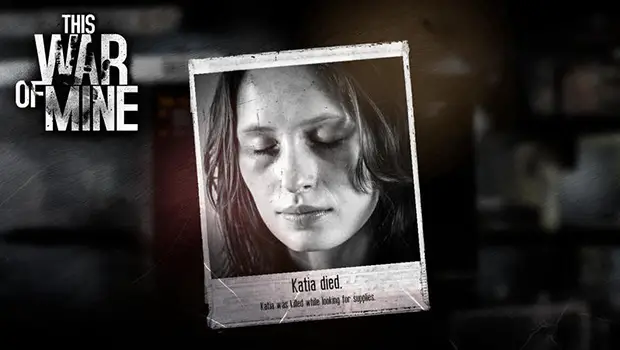

This War of Mine is a war game, but it isn’t about warriors or heroes. There are no great struggles, but it makes the small struggles matter. Instead of putting the player in the role of intrepid adventurer or armor-plated supersoldier, This War of Mine puts the player in control of the lives and decisions of a group of war refugees. There are no heroes, only victims.

On the surface, This War of Mine is a survival strategy/simulation game. You rebuild and improve an abandoned house in the daytime, and at night you scavenge for supplies. The mechanics are simple – certain supplies are required for certain improvements. You need wood to build a bed, weapon parts to build a saw, water and meat to cook, and bait to set traps. At night, you sneak around different areas in varying states of destruction – a field hospital set up in the ruins of an old one, a flophouse for the lowest vagrants, the home of an old husband and wife just trying to hold on – sneaking around, avoiding conflict, and grabbing as many supplies as you can carry. The controls are simple. It’s quite literally point and click.

The gameplay, however, is almost unimportant, except that it forces you to make choices, hard, brutal choices. Food is always scarce, and when I played through the game, my characters were always starving. I saw them complaining every day about their empty stomachs. I could either let my characters starve, or rob an old couple blind. I took everything from them as they watched, helpless, begging for me to leave them something. It put a knot in the pit of my stomach and I had to stop playing for the day. When I picked the game up again, my characters were horrified at what they had done.

The most chilling moment was when I had a character kill a man. It was the first time I encountered another person, and I didn’t know how they would react. I was scared. I didn’t want to lose, didn’t want my character to die. So before the vagrant I ran into could do anything, I beat him to death with a shovel. In the next room, there were even more vagrants who all simply ignored me. When I returned home, the character who killed the vagrant was depressed. She was wracked with guilt, and so was I.

This is the success of This War of Mine. It puts you into the mind of the starving, the dispossessed and the desperate. It shows you that survival is not easy, that the truest victims of war are not fallen soldiers but the innocents left behind. This War of Mine isn’t just a reaction to the endless stream of war-glorifying shooters, it is a response to all war and anti-war art that focuses on combatants as the sole recipients of horror. Wilfred Owen, Kurt Vonnegut, Tim O’Brien, all hallowed names in the annals of war literature and criticism. Yet they all focused on the burdens borne by the soldiers and overlooked, as many do, the civilians stuck in the boot-churned mud. This War of Mine challenges literature’s view on war and in doing so become literature itself. It is so rare that games become art, but the sickening feeling in my stomach every time I see one virtual character mourn another tells me that this one is, in fact, a work of art.

Hardcore?

As Hardcore as it gets.

Entertainment becomes art in this survival game about the human tolls of war. Your heart will break with every tough choice you make to keep your war refugees alive. At times, This War of Mine is downright hard to stomach, but it is a masterpiece all the same.