If you want to write about games professionally, odds are you’re going to have to churn out more than a few reviews. Reviewing games is not all game journalists do, and I’ve gone long stretches doing only features or guides, but they ultimately make up the bulk of content for most gaming sites and publications, and you’re going to need to get good at keeping them fresh and interesting, even when the game you’re covering is not.

Reviews are also probably one of game journalism’s most misunderstood forms of writing. People often think that the purpose of a game review is only give an opinion; to decide for the reader if a game is good, and at their worst, this is exactly what reviewers do. But readers peruse reviews for two reasons: to be entertained and to decide for themselves if a game is right for them. Never lose sight of these two goals, and always write for your audience. If you aren’t being entertaining or informative, you’re not giving people what they want.

Before You Write

Part of writing a good review is preparation. For almost any review, the vast majority of your time will be spent playing the game. These days that usually means 10 hours all the way up to 40 hour RPGs. Particularly with narrative games, it’s vital to play a game all the way to the end. If a game doesn’t have an end, you should make sure to see as much of the content as is reasonably possible before deciding to write.

But prep shouldn’t end with playing the game. Know who developed a game. Read the credits, look up what key figures have worked on previously. If a game is part of a series or based on a license, learn what you can about it, and, if possible play some other games for context, or at least read reviews. If you’re not especially familiar with a game’s genre, try your best to familiarize yourself with the full context of what you’re writing about.

You should be more qualified than most to write about this game by virtue of your knowledge and experience, as well as your communication skills. If you aren’t an expert, become one. Research is often the key to finding the angle that can make a review interesting or insightful in a way that a mere opinion is not.

The Opening

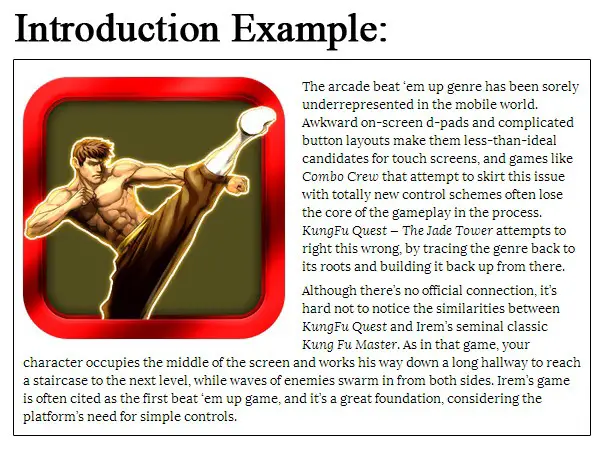

The most important part of a review is the opening paragraph. Most amateur reviews start by simply describing the game, or even setting up their conclusions. This is poor framing, because it does nothing to engage the reader.

A good writer, just like a good storyteller, tries to establish conflict, and leaves it unresolved until later in the review. In most cases, this means establishing why this game is unique or interesting, and why its quality ultimately matters. A game might be a strong comeback for a flagging series, or it might champion a genre that’s underrepresented on the platform. It’s up to you to find that angle. This can often be challenging, because most games are, in fact, not that unique. Good reviews and bad reviews are always the easiest to write. Mediocre reviews of generic games are the real challenge.

As you write more reviews, it’s important not to be formulaic. If you think of the opening paragraph as the start of a story, it can help to avoid familiar patterns. You can begin with a personal anecdote, a quote, or anything else that can help to frame the piece as significant.

When you write your opening, you should also be visualizing your closing. The best reviews establish the seed of an idea in the beginning, and leave it unresolved, develop that idea throughout the body of the review, and then return to it in their conclusion. This kind of flow ensures the reader will want to reach the end of the article.

The Body

The most common mistake made by amateur reviewers is writing with a checklist. This tradition harkens back to the dark ages of game magazines, which were often written by people who knew a lot more about games than they did about writing. They would divide the review into sections – sometimes with their own headers and scores – to discuss set topics like graphics, sound, and controls, and do the same for every review.

This is bad writing. Throw out the template. In the same way that your introduction should establish what makes a game unique or interesting, your review should embellish that. In many cases this will, indeed, involve discussing the game’s graphics or its soundtrack, but not in every review.

A review should flow conversationally, detailing the points that are pivotal to this experience. If something doesn’t leap to mind when plotting your way through a review, it’s probably alright to skip in most situations.

The notable exception to this, of course, is when the audience’s interest might differ from your own. You aren’t writing for yourself, and your readers might want to know about things outside of the scope of your own interest. For example, I might not be particularly interested in the competitive multi-player modes, but for many these might be a bigger draw than the single-player. It’s important to give your readers the relevant information they need to decide if a game is right for them.

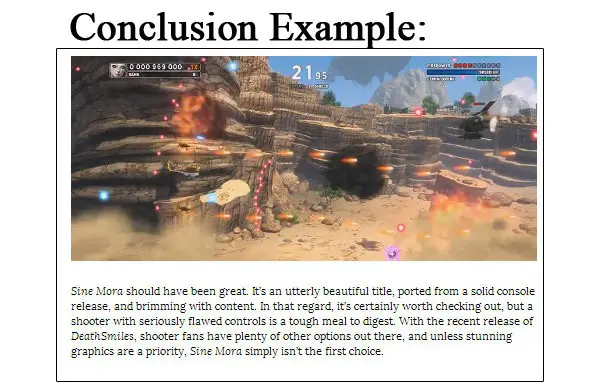

Wrapping Up

Ideally, you should connect the end of your review to the conflict you’ve established in the beginning. You want to bring the narrative to a close and come to a clear conclusion, but it’s important to always remember to leave room for the reader to draw his or her own conclusion as well.

Reviews tend to draw a lot of hate from those that disagree with their conclusion. Jeremy Dunham, former Editor-in-Chief of IGN, once told me that readers judge the quality of a review by how well it matches their own feelings. I feel this doesn’t have to be the case if you remember to think outside of yourself.

Ideally, your review should still be helpful to someone whose tastes or experiences are different than your own. You can explain why you didn’t like a game, while still adequately acknowledging its merits and the sort of person who might appreciate the game. Likewise, you can praise a game while still giving readers the information to decide if it’s not their thing.

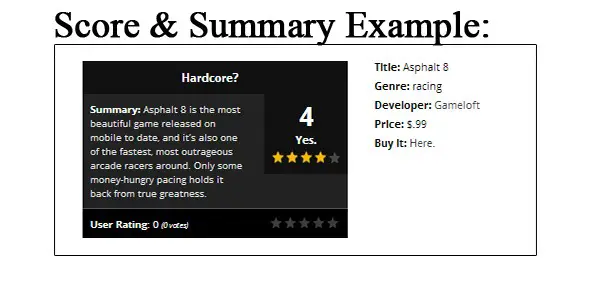

The Score

Almost no writer really likes assigning a score to a game. Often a game’s merits are complex and reducing pages of writing to an arbitrary number can seem to devalue the review itself. But the fact is, you have to do it. Readers want a score, aggregators need a score, and almost any publication you write for is going to expect it.

Scoring a game is not scientific. It’s arbitrary. The best way to think of a score is as a reflection of your mood. It’s just a reflection of how much you enjoyed a particular game compared to other games. Over time, it will become clearer where a game sits compared to everything else you’ve written.

Writing a Strap line

A strap line is a small tease under the review title designed to hook the reader. The length varies depending on the publication, but the intent is always the same. Generally, a strap line should include a bit of intrigue without giving away too much of the review’s conclusion or content.

Most importantly, you should avoid obvious puns or clichés here. Don’t say “Gran Turismo revs up for racing action,” or “Street Fighter smashes through the competition.” This is just hack writing, and it won’t grab anyone’s attention, except for the rolling eyes of anyone who reads too many game reviews.

Don’t miss Travis’s article On Being a Game Journalist >>>